Prompted by an oldish Microsoft blog about how too many people focus on password complexity, this blog discusses how much passwords matter for security, relative to other protections such as MFA and Password Managers.

Passwords Don’t Matter

I recently came across this interesting 2019 article from Microsoft. It’s interesting chiefly for making a somewhat counter-intuitive argument about passwords: specifically that password complexity doesn’t matter anymore. It’s an interesting and worthwhile article, and it’s always worth trying to take a fresh look at the old security tropes. It’s also backed up by good data. The context for their argument is stated in the first paragraph:

Focusing on password rules, rather than things that can really help – like multi-factor authentication (MFA), or great threat detection – is just a distraction.

Your Pa$$word doesn’t matter, Alex Weinert, Microsoft.

It’s hard to argue with this point. But in the defence of everyone outside of the security industry, collective advice on passwords has changed frequently over the last few years; there’s still a lot of confusion about best practice, and I wouldn’t blame someone who thought that changing passwords every 90 days was still advisable.

The Microsoft article details a number of different attack scenarios, and evaluates whether the actual password matters in the attack. For the majority of the attacks, which include credential stuffing, phishing and brute forcing, the password complexity doesn’t matter, as the attacker either has the plaintext password already, or can obtain it relatively easily.

So the argument boils down to “if you don’t have good password practices, then your actual password doesn’t matter”. i.e. if you aren’t using a password manager to generate and remember strong passwords, you might as well give up on complexity and just use password1. This is clearly stated:

The point is – your password, in the case of breach, just doesn’t matter – unless it’s longer than 12 characters and has never been used before – which means it was generated by a password manager.

Your Pa$$word doesn’t matter, Alex Weinert, Microsoft.

The longer form of the argument made should be: password complexity doesn’t matter if you’re using a password manager and MFA. Or, to put it another way, password complexity shouldn’t matter, because you use a password manager and MFA for everything.

With a password manager, complexity and length are no longer an issue worth considering as it’s just a setting in the application. Even the default password settings for most password managers will generate stronger passwords than most people would invent themselves. In fact, you’re more likely to find a password being rejected for being too long or too complex by sites and applications with outdated password setup procedures. And with MFA, compromised passwords still don’t allow an attacker to get in.

So we don’t have to care about password complexity at all! But then…

Actually they do matter. A bit. Sometimes.

Of course, it’s not quite that simple. We’ve had customers with all levels of account security practices, including some who still don’t have MFA on every business-critical system. To them, password complexity does still matter. But, as per our central argument, not more than applying MFA.

If I had to set a priority for improving account security, it’d be the following order:

- Apply MFA using an authenticator app (the Google or Microsoft apps, or Authy, or integrated solutions like Okta and Duo), or better yet, hardware authentication tokens.

- Encourage or enforce the use of a Password Manager, for example centrally managed products such as BitWarden or 1Password.

- Encourage or enforce good practices for using both of the above.

In this sequence, encouraging better quality passwords would be a useful stop-gap measure between steps 1 and 2, but is less important than the stated steps.

This priority is somewhat arbitrary. You could argue either way for the relative importance of password managers and MFA, and be correct in different situations. An example argument against the above order would be: given that not all sites support MFA, maybe adopting a password manager is the more effective first step.

But maybe the answer is somewhere in the middle: they’re both as important as each other. MFA wouldn’t be a requirement if all passwords were safe (no systems storing password hashes were breached, and those hashes couldn’t be cracked in a useful time period); and password managers wouldn’t be necessary if everything supported MFA.

There’s always more

It’s also not as simple as saying “just turn on MFA”. For example, there’s a lot of sniffiness in the InfoSec industry about one-time passwords for MFA, which mostly comes from legitimate security concerns about SMS-based MFA. Because of the dangers of SIM swapping, and the lack of security with some mobile networks, it’s definitely preferable to use a more secure MFA mechanism. For a recent example of problems with SMS, see a recent Vice article about redirecting SMS for $16. But clearly even SMS MFA is better than no MFA at all.

Even better, of course, are authenticator apps and hardware tokens (such as the FIDO2 compliant Google Titan Keys, or the newer range of Yubikeys). We advise customers to use hardware tokens, at a minimum, for admin or privileged accounts.

And of course, account security isn’t just about Password Managers and MFA. We also encourage the use of conditional access policies and other account security measures such as limiting invalid login attempts, applying account lockouts, and monitoring for login abuse or unusual activity.

A Perfect (Authentication) World

If everyone in the world only ever used strong passwords (long and complex passwords generated by - and stored in - a good password manager, and used uniquely per account and service) there’d be no economy for breaking password hashes. Therefore password spraying and brute-force attacks wouldn’t be worthwhile, as the only possible password attack against an individual account would be to use the correct stolen plaintext password, for example if obtained from a successful phishing attack.

But we’re not there yet, and may not ever be. Unfortunately, the marketplace for stolen passwords and credentials is as big as ever. We spent some time researching it last year, to help with this investigation by the Consumer Association (aka Which?), and tried to map out the ecosystem for stolen passwords.

The Stolen Password Ecosystem

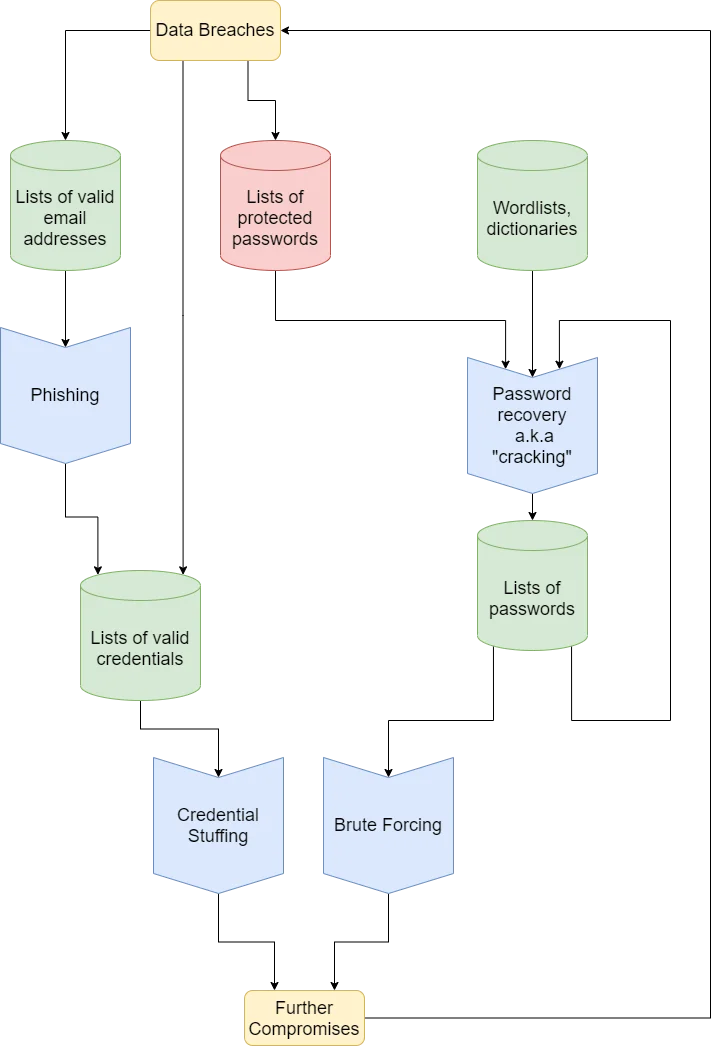

The output of previous data breaches, like email addresses and protected passwords, are used to mount further attacks that lead to more data breaches, which result in more compromised addresses and passwords. This cycle is illustrated in the diagram below:

The economy for stolen passwords has had an affect on attacker behaviour; many classes of attacks are aimed solely at stealing credentials, not so that they can be directly used in an attack, but to simply sell them on. Where stealing credentials used to be the first part of an attack that aimed to steal data or control systems, now it is itself an attack.

Thankfully there is some positive news: whilst the number of breaches isn’t necessarily going down, the number of breaches of plaintext passwords probably is, as best practices for protecting stored passwords are more widely adopted. That means password complexity, the only defence against it being cracked, is still important in some cases, but decreasingly so. Plus, in a true race to the bottom, it’s probably more profitable to use those GPU rigs for crypto-currency mining, instead of cracking password hashes.

Links

- Your Pa$$word doesn’t matter

- The follow-up blog, on MFA issues

- NCSC: Password administration for system owners

- Microsoft Password Guidance

- BitWarden: Install and Deploy

- 1Password Business and Enterprise

- Okta MFA

- Duo Security

- Google Titan Keys

- Yubikey 5 series